Psychosomatic osteopathy - Holistic health redefined

Psychosomatic osteopathy - holistic understanding, differentiated treatment

Psychosomatic osteopathy, as taught at the Liem Institute, combines manual techniques with psychological sensitivity and recognizes the human being in all its complexity.

Health is more than the absence of symptoms – it is a dynamic process that includes physical, emotional, mental and social levels.

In psychosomatic osteopathy, as developed by the Liem Institute, the focus is on the person as a whole.

This view makes it possible:

- more precise diagnoses for chronic or “unexplained” complaints,

- more sustainable treatment successes,

- and a deeper therapeutic relationship with the patient.

The body is more than just a carrier of symptoms – it tells stories.

The work at the Liem Institute is about reading these signals, using other tools to capture the whole person and their relevant contextual factors for diagnosis and resources, and using targeted osteopathic treatment to support the ability to regulate at all levels.

Every touch becomes a diagnostic and therapeutic intervention – delicate, respectful, effective.

Over the decades, psychosomatic osteopathy has been influenced by various schools of thought – from classical osteopathy and body psychotherapy to systemic and neurobiological approaches.

Torsten Liem has brought these perspectives together in a coherent model that is taught and further developed at the Liem Institute today.

Many physical symptoms have an emotional or social component.

Without taking these levels into account, treatment often remains superficial.

Psychosomatic integration opens new therapeutic doors – even for chronic pain, functional disorders or diffuse complaints.

The five pillars of training at the Liem Institute

- Diagnosis of regulatory capacity: recognizing what keeps the system stable – and what brings it into imbalance.

- Understanding psychosomatic patterns: holistically classifying body, emotion and context.

- Physical contact with respect: every touch is diagnostic and therapeutic at the same time.

- Integration of current research: combining clinical experience with new scientific findings.

- Self-reflection of the therapist: Understanding and developing one’s own therapeutic attitude as part of the effect.

In each module of the PSO training at the Liem Institute, theoretical knowledge is deepened through practical exercises.

The Institute places particular emphasis on experiential learning: self-awareness, supervision and interactive small group work create a lively, practice-oriented learning process.

The methods of the Liem Institute are particularly suitable for osteopaths who want to achieve more depth, effectiveness and human clarity in their work.

Psychosomatic osteopathy, as it is taught here, is not a rigid concept – but a living toolbox for a new generation of holistically minded therapists.

The body is a mirror of the soul - every touch tells a story.

Origin of psychosomatic osteopathy

Through clinical challenges in practice, I was increasingly motivated to gain a deeper understanding of health and disease. Especially in the case of complaints due to protracted unresolved problems and chronic allostatic influences, my previous osteopathic approaches and techniques were usually not sufficient to support patients towards long-term health.

On the one hand, this was due to the fact that several systems – such as the hormonal, metabolic, immune and digestive systems and the psyche – were imbalanced at the same time. On the other hand, it could be attributed to the fact that patients increasingly showed not only functional disorders but also anatomical changes, such as fibrosis, a breakdown of glucocorticoid receptors in the hypothalamus or insulin receptors in muscle cells, or fat deposits in the liver.

In addition, there was the experience that osteopathic treatment of somatic dysfunctions as well as approaches of functional energetic treatments were not necessarily able to resolve inflexible patterns in the patient’s experience – be it cognitive, limbic or neurovegetative patterns of experience – as well as metabolic, endocrine and immunological relationships. In addition, patients were mostly passive in the osteopathic treatment process. Structural as well as functional or energetic treatment approaches were mostly unsuitable to support patients in learning proactive behavior with regard to their life context and changing lifestyle habits, although this is an essential factor for recovery and especially for health maintenance.

I then began to study other underlying mechanisms of action. Over the last 20 years, this has resulted in multiple new osteopathic diagnostic and therapeutic approaches and techniques as well as modified and expanded principles of treatment. I have termed these new approaches and techniques “psychosomatic osteopathy”. The majority of these mechanisms of action are based on studies conducted over the last 30 years. They were therefore not accessible to A.T. Still and the early osteopaths, so they could not base their approaches on these mechanisms of action.

These different currents have been brought together at the Liem Institute to form an integrative training approach that combines theory, clinical application and therapeutic attitude.

In psychosomatic osteopathy, we not only look for the cause, but also for the why.

Risk factors for complaints from a PSO perspective

When patients come for an osteopathic consultation, their complaints, disorders and somatic dysfunctions are just the tip of the iceberg. Underneath – often relatively unnoticed – there is a multitude of longer and shorter-lasting, more or less interacting, mutually reinforcing or diminishing risk factors, mechanisms of action and allostatic influences. These are differentiated and diagnosed as soma-physiology-experience-context dysfunction patterns in PSO. In treatment, the focus is simultaneously on the patient’s resources, including soma-physiology-experience-context dynamics and many other aspects, as well as on the inhibition, relativization, resolution and integration of risk factors.

Dysfunction dynamics from the perspective of PSO

The particular organization of our physicality and personality allows us to perceive the world in a certain way and gives us the opportunity to live in the world and take care of our well-being. This dynamic interplay of person and context has developed evolutionarily and genetically, as well as through transgenerational, epigenetic and anthropogenic influences. Our clinical hypothetical working model refers to the fact that both positive or life-enhancing and negative or harmful contextual and environmental influences can occur throughout life

Allostatic influences in the treatment of PSO

Harmful influences can lead to allostatic reactions, dysfunctional psychophysiological and structural adaptations as well as rigid, outdated conditioning and put a strain on the person’s physiology, reaction and experience patterns, reduce the ability to react adequately and flexibly to current challenges in life and increase the risk of symptoms and illnesses. It is not only the strength and duration of the harmful contextual factors that play a role, but also the time of their occurrence. Early periods of ontogenetic development are particularly susceptible. The earlier in life (including the prenatal period) protective and survival reactions have to be initiated, the more profound inflexibilities and dysfunctional conditioning can result. Polymorphisms also play a role in susceptibility to harmful contextual factors.

The inflexibilities resulting from the protective and survival reactions vary depending on the period of life and the intensity and duration of the harmful influences. The analogy of the hardware and software of a computer can be used to illustrate this: The earlier harmful influences occur, the sooner more essential structures can be damaged.

- From conception, the hardware can be affected, i.e. the genetics.

- Fetal programming is illustrated by the functioning of the BIOS (which acts as an intermediary between operating systems and hardware). In chronic stress, processes of cortisolemia and cortisol resistance affect the unborn child with numerous disease risks in later life.

- Peri- and postnatal processes could be symbolized by influence on the driver of a computer that controls hardware devices. Birth processes, for example, have an effect on conditioning in the raphe nuclei with regard to serotonin production.

- By the age of 4, harmful influences can affect the operating system that manages the interaction of a computer’s hardware and software components. Early childhood stress shows increased disease risks in adulthood, as interacting dysregulations in multiple physiological systems impair the ability to respond flexibly to stressful contexts. For example, there are persistent and profound effects on prefrontal, hypothalamic, amygdala and dopaminergic circuits.

- Disruptive factors at preschool age have an effect on computer programs.

Health problems during this period are perpetuated, for example, by psychosocial mechanisms. In summary, it can be stated that influences during childhood are associated with the development of certain phenotypes, which in turn predispose to certain allostatic reaction patterns and clinical pictures.

Treatment structure in PSO

The soma-physiology-experience-context dysfunction patterns (SPEKD) underlying and associated with the clinical symptoms are treated in a clearly defined setting. The treatment structure in psychosomatic osteopathy is roughly divided into 5 phases:

01.

Therapeutic relationship

A clear, stable, transparent therapeutic relationship that supports healing is the basis for all further measures. The focus is on interpersonal interaction and resonance, empathy, solution strategies for obstacles to treatment and attunement to the treatment.

02.

Diagnostics

The tissue and physicality reflect the individual’s interconnectedness, views and conditioning. Repressed contents of consciousness or body energies are also expressed in the tissue. By means of palpation, certain parts of the underlying mechanisms of action of symptoms, complaints and somatic dysfunction patterns can be identified. However, further specialist knowledge and perception tools are required in order to be able to correlate the palpatory findings with the influences mentioned. At the same time, some of these influences cannot be diagnosed by palpation. Further diagnostic skills are required here, such as anamnesis, assessment of behavior, facial expressions and, if necessary, questionnaires, laboratory findings, etc.

03.

Stabilization phase

This includes a variety of skills, e.g. for the verbal accompaniment of palpatory approaches, and in particular osteopathic manual procedures for stabilization and co-regulation.04.

Integration/confrontation phase

The tissue and physicality reflect the individual’s interconnectedness, views and conditioning. Repressed contents of consciousness or body energies are also expressed in the tissue. By means of palpation, certain parts of the underlying mechanisms of action of symptoms, complaints and somatic dysfunction patterns can be identified. However, further specialist knowledge and perception tools are required in order to be able to correlate the palpatory findings with the influences mentioned. At the same time, some of these influences cannot be diagnosed by palpation. Further diagnostic skills are required here, such as anamnesis, assessment of behavior, facial expressions and, if necessary, questionnaires, laboratory findings, etc.05.

Integration in everyday life

The osteopathic consultation is like a therapeutic uterus. The successful changes achieved there must prove themselves in everyday life. The treatment is also tailored to the extent to which the therapeutic impulses have an effect on everyday life. In the case of chronic complaints, healing or, if necessary, implementation in everyday life occurs gradually and is an essential part of the therapeutic effect.

These 5 treatment phases are not strictly separated from each other. They merge into one another and influence each other.

During treatment, osteopathic approaches are developed and applied in order to activate resource-oriented mechanisms of action or to inhibit dysfunctional mechanisms of action. In addition, patients are given access to attitudes, postures and deep needs that were previously not conscious and accessible. This is done by helping them to consciously experience specific reaction patterns with regard to therapeutic touch.

These treatment approaches consist of a dosed and finely tuned real-time interaction of multimodal interventions that work together. These include, for example, palpatory, acoustic, visual, cognitive, emotional and neurovegetative interventions as well as active and passive movement, interoceptive focus and breathing. The aim of these interventions is to integrate the aforementioned aspects, such as anatomical-physiological interactions, perceptual or sensorimotor states and dynamics.

Patients are supported in a co-regulatory way to perceive, differentiate and integrate these acting forces and their relationship to their life context by means of osteopathic palpation.

Co-regulation and feedback loops in PSO

In PSO, therapistsact as co-regulatorsby observing the neurovegetative, limbic and cognitive reactions of their patients throughout the treatment. This is done, for example, on the basis of facial expressions, gestures, behavior, posture, breathing, pulse, pupil and speech (in terms of content, emphasis, emphasis, tone and rhythm).

The resolution of dysfunctional patterns, the processing and integration, take place in a dynamic state of balance and flow. This state is characterized by effortless attention and an unforced, spontaneous, emergent experience of the patient. In the integration phase (in contrast to the stabilization phase), the patient has dosed contact with triggers and dysfunctional aspects of SPEKD. The treatment approaches take place in a mild neurovegetative arousal, possibly also in a dynamic balance between negative and positive emotions and between impulse inhibition and activation. At the same time, it is essential to avoid any form of retraumatization.

It is therefore important to identify the patient’s proximal learning zone on the basis of the therapeutic relationship. This refers to the level of integration that is accessible to the patient. In addition, contact with the patient’s subjective experience must be maintained throughout the treatment. This means that stabilization resources can be individually adapted and applied in doses as co-regulation during the integration or confrontation phase.

During treatment, many other finely tuned aspects of intervention are used in addition to the touch intervention. The patient’s proactivity is actively encouraged and the inner experience is used as a therapeutic tool and inherent part of the treatment. This includes a variety of interacting multimodal, holarchic top-down and bottom-up interventions and responses. The aim is to activate a state of flow that triggers inner working processes. These processes involve multiple mechanisms of action and feedback loops. For example, this process can result in evoked, emergent new postures, activity patterns in body regions and changes in muscle tone, breathing, pulse, circulation and other physiologies.

By means of mindfulness support, patients can be helped to perceive associated new bodily sensations, interoceptions, proprioceptions and other somatic markers. They can also identify interactions with beliefs, belief patterns and feelings. Possible changes can also arise from this, and more flexible mechanisms of action can be established. Finally, potentially expanded co-regulations and levels of perception can be acquired in the context of life.

In the context of PSO, therapists must pay attention to a number of interactions, such as understanding the mechanisms of action and interactions of the body systems and organs as well as the dynamic influences of contextual factors and accumulating risk factors in relation to SPEKD. These interactions must be taken into account throughout the treatment and co-regulations applied where necessary. In addition, the patient’s awareness of the associated multiple interactions and the skills of co-regulation and self-regulation should be promoted during osteopathic treatment.

Principle of holarchies and holonic dynamic networks

The principle of holarchies and holonic dynamic networks is characterized by the view that there are no separate wholes, but that each whole (holon) consists of smaller parts (subholons) on the one hand and is part of a larger whole on the other. The term “holon” was coined by Arthur Koestler. The hierarchical arrangement of holons is referred to as a holarchy. This holarchic organization can be traced back to evolutionary and ontogenetic dynamics.

PSO is based on the assumption that life in general and homeostatic and allostatic processes in particular are shaped by several interacting holons. In the human body, a cell can be regarded as an autonomous unit on the one hand and as part of a tissue on the other. This holistic organization is characterized by self-organization and autonomy at all levels. Accordingly, the patient or a specific pattern of dysfunction, such as a tense muscle, is viewed on the one hand as a whole, i.e. as a whole in itself and of itself, and on the other hand always as part of something else or as part of a larger whole.

In the case of complaints, a whole has shifted dysfunctionally in a certain way in relation to its parts (subholon) or a part in relation to a whole, e.g. a tissue in relation to an organ or an overreacting immune system in relation to the person. This is diagnosed as a specific dysfunction pattern or dysfunction complex, to which the therapist enters into resonance. Thus there are dynamic, clinically relevant part-whole relationships that characterize the entire palpatory approach. For example, a muscle as a whole is also part of other wholes, such as the iliopsoas muscle on the one hand as a whole and on the other hand in relation to the caecum region, posture, sedentary lifestyle or insulin resistance.

The principle of holarchies is also expressed in multiple, mutually influencing bottom-up and top-down dynamics and patterns. A further basis of psychosomatic osteopathy is that health and illness take place on dynamically developing, different hierarchically structured, interacting levels. The identification and differentiation of these processes of adaptation, regulation and allostasis during diagnosis enable individually adapted osteopathic approaches in the clinical context. A distinction can also be made between lines of development and levels.

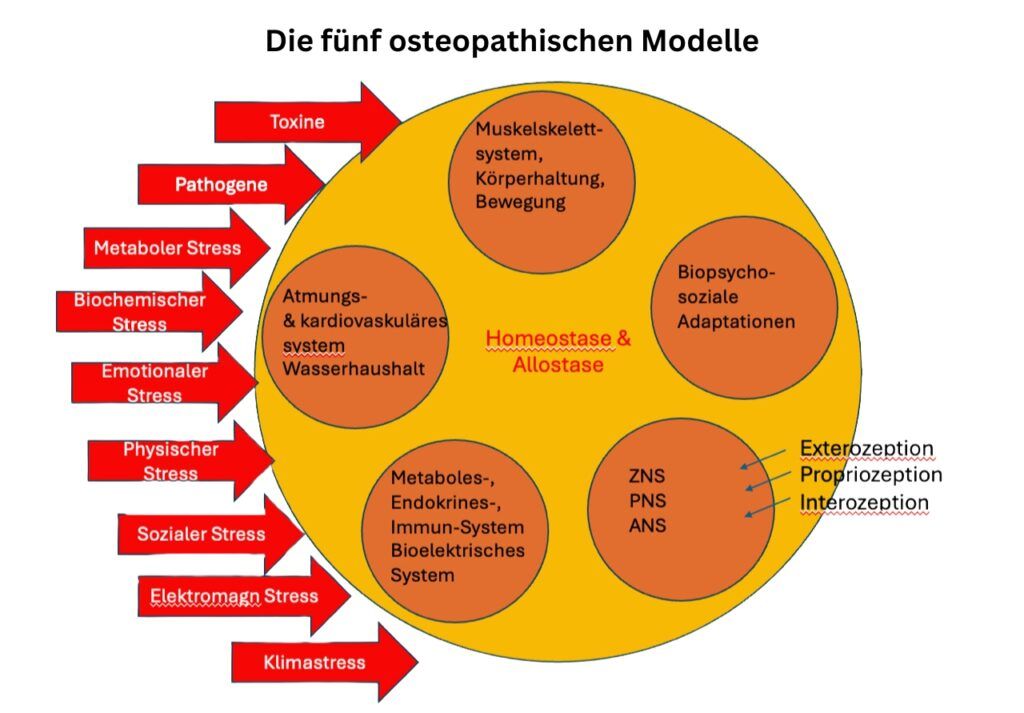

The five osteopathic models

The five osteopathic models were developed for clinical application on the basis of osteopathic principles by a group of trainers of the Educational Council on Osteopathic Principles (ECOP) in 1987 and were first presented by Greenman (1987, 1989) and Mitchell Jr. (Retzlaff 1987) and later further differentiated by Hruby (Hruby 1991; Hruby 1992) and further developed by me. All five areas and their interactions are not only examined diagnostically in relation to each other, but also with regard to homeostatic allostatic contextual influences and treated using multiple osteopathic approaches (Liem et al. 2021). It is essential that possible allostatic or dysfunctional reactions are caused by contextual changes, such as toxogenic, pathogenic, metabolic, biochemical, emotional, physical, social or electromagnetic stress factors. For this reason, the reciprocal dynamics between person and context must be taken into account in the diagnosis and treatment.

The illustration shows the five osteopathic models that take into account different levels and systems of the body, including the musculoskeletal system, the respiratory and cardiovascular systems, biochemical and neurological processes and biopsychosocial adaptations. The models illustrate the influence of various stress factors, such as toxins, metabolic, physical and emotional stress, on the body’s homeostasis and allostasis. The aim is to bring these systems into balance through osteopathic treatments and to promote the body’s ability to adapt.

Indications for the approaches of psychosomatic osteopathy

The indications are the same as for any other osteopathic treatment, supplemented by a few other complaints, e.g:

- SPEKD

- Chronic pain conditions

- Secondary chronic injuries

- Stress-associated and multimorbid clinical pictures

- Chronic functional disorders with psychological components, e.g. learning disorders

- past stressful experiences, memories or significant parts thereof occurring during osteopathic treatment or palpation

- Optimization of the individual’s proactivity and adaptivity in relation to their intersubjective and biosocial life context – based on ego experiences, needs, emotions, life goals, self-efficacy, beliefs, dispositions, etc.

- Increase in awareness and proactivity with regard to habits, lifestyle factors and beliefs in connection with symptoms

- any complaints and diseases accessible to osteopathy

- Negative emotions, fears, phobias and dysfunctional emotion regulation

- Addictive behavior

- Processing biographical backgrounds for somatic dysfunctions

- Current triggers and habitual patterns that restrict everyday life

- Allergies

- irrational negative cognitions

- Traumatization

All contents and requirements are based on the curriculum of the Liem Institute for Psychosomatic Osteopathy.

© 2025 Torsten Liem. All rights reserved. Made by DigitalUplift